Lesson Outcomes – After reading this lesson, you should be able to:

Lesson Outcomes – After reading this lesson, you should be able to:

- discuss the nature of stress and anxiety (what they are and how they are measured),

- identify the major sources of anxiety and stress,

- explain how and why arousal- and anxiety-related emotions affect performance, and

- compare ways to regulate arousal, stress, and anxiety.

Jason comes to bat in the bottom of the final inning with two outs and two men on base. With a hit, his team will win the district championship; with an out, his team will lose the biggest game of the season. Jason steps into the batter’s box, his heart pounding, and butterflies in his stomach, and has trouble maintaining concentration. He thinks of what a win will mean for his team and of what people might think of him if he does not deliver. Planting his cleats in the dirt, Jason squeezes the bat, says a little prayer, and awaits the first pitch. If you’re involved in athletics, you have probably faced the elevated arousal and anxiety of situations such as Jason’s. Consider the following quote from Bill Shankly, former manager of Liverpool Football Club, regarding the importance of winning and losing in competitive sport:

Although pressure is all too real in military and emergency services settings, where life and death can truly rest on one’s decisions, coping skills, and eventual performance (e.g., Janelle & Hatfield, 2008), success and failure in competitive sport—especially at high levels—can also produce extreme anxiety. History is replete with athletes who have performed exceedingly well under pressure and those who have performed exceedingly poorly. It is no surprise that the relationship between competitive anxiety and performance has been one of the most debated and investigated topics in sport psychology. Sport and exercise psychologists have long studied the causes and effects of arousal, stress, and anxiety in the competitive athletic environment and other areas of physical activity. Many health care professionals are interested in both the physiological and psychological benefits of regular exercise. Does regular exercise lower stress levels? Will patients with severe anxiety disorders benefit from intensive aerobic training and need less medication? Consider how stress provoking learning to swim can be for people who have had a bad experience in water. How can teachers, coaches and trainers reduce this anxiety?

Defining Arousal and Anxiety

Although many people use the terms arousal, stress, and anxiety interchangeably, sport and exercise psychologists find it important to distinguish between them. Psychologists use precise definitions for the phenomena they study to have a common language, reduce confusion, and diminish the need for long explanations.

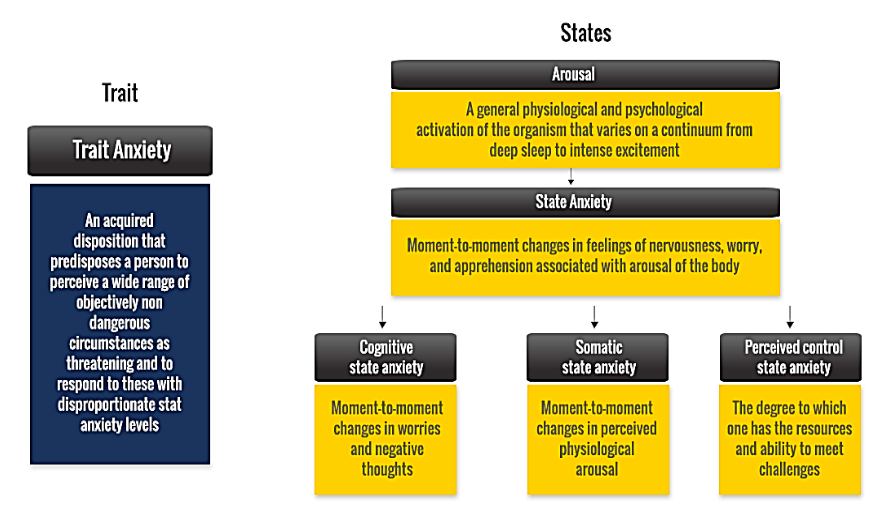

Arousal

Arousal is a blend of physiological and psychological activity in a person, and it refers to the intensity dimensions of motivation at a particular moment. The intensity of arousal falls along a continuum ranging from not at all aroused (i.e., comatose) to completely aroused (i.e., frenzied. Highly aroused individuals are mentally and physically activated; they experience increases in heart rate, respiration, and sweating. Arousal is not automatically associated with either pleasant or unpleasant events. You might be highly aroused by learning that you have won $10 million. You might be equally aroused by learning of the death of a loved one.

Anxiety

In a general sense, anxiety is a negative emotional state characterized by nervousness, worry, and apprehension and associated with activation or arousal of the body. (Although anxiety is perceived as negative or unpleasant, it does not necessarily affect performance negatively. In sport settings, anxiety refers to “an unpleasant psychological state in reaction to perceived stress concerning the performance of a task under pressure. Anxiety has a thought component (e.g., worry and apprehension) called cognitive anxiety. This coaching certification specifically helps you teach your clients/athletes how to manage anxiety.

It also has a component called somatic anxiety, which is the degree of physical activation perceived. In addition to the distinction between cognitive and somatic anxiety, it is important to distinguish between state and trait anxiety.

State Anxiety

At times we refer to anxiety as a stable personality component; other times we use the term to describe a changing mood state. State anxiety refers to the ever-changing mood component. It is defined more formally as an emotional state “characterized by subjective, consciously perceived feelings of apprehension and tension, accompanied by or associated with activation or arousal of the autonomic nervous system. For example, a player’s level of state anxiety changes from moment to moment during a basketball game. She might have a slightly elevated level of state anxiety (feeling somewhat nervous and noticing her heart pumping) before tip-off, a lower level once she settles into the pace of the game, and then an extremely high level (feeling very nervous, with her heart racing) in the closing minutes of a tight contest.

Cognitive state anxiety concerns the degree to which one worries or has negative thoughts, whereas somatic state anxiety concerns the moment-to-moment changes in perceived physiological activation. Somatic state anxiety is not necessarily a change in one’s physical activation but rather one’s perception of such a change. Research also suggests that there is a perceived control or regulatory component of state anxiety; that is, the degree to which one believes one has the resources and ability to meet challenges is an important component of state anxiety as well (Cheng et al., 2009).

Trait Anxiety

Unlike state anxiety, trait anxiety is part of the personality, an acquired behavioral tendency or disposition that influences behavior. In particular, “trait anxiety predisposes an individual to perceive as threatening a wide range of circumstances that objectively may not actually be physically or psychologically dangerous. The person then responds to these circumstances with state anxiety reactions or levels that are disproportionate in intensity and magnitude to the objective danger. For instance, two field-goal kickers with equal physical skills may be placed under identical pressure (e.g., to kick the winning field goal at the end of the game) yet have entirely different state anxiety reactions because of their personalities (i.e., their levels of trait anxiety). Devante is more laid back (low trait-anxious) and does not perceive kicking the game-winning field goal as overly threatening. Thus, he does not have more state anxiety than would be expected in such a situation. Elija, however, is highly trait- anxious and consequently perceives the chance to kick (or, in his view, to miss) the winning field goal as very threatening. He has tremendous state anxiety—much more than we would expect in such a situation.

Measuring Arousal and Anxiety

Sport and exercise psychology coaches measure arousal, state anxiety, and trait anxiety in various physiological ways and through psychological measures.

To measure arousal, they look at changes in physiological signs: heart rate, respiration, skin conductance (recorded on a voltage meter), and biochemistry (used to assess changes in substances such as catecholamines).

These psychologists also look at how people rate their arousal levels using a series of statements (e.g., “My heart is pumping,” “I feel peppy”) and numerical scales ranging from low to high. Such scales are referred to as self-report measures of arousal and anxiety.

To measure state anxiety, psychologists use both global and multidimensional self-report measures. In the global measures, people rate how nervous they feel using self-report scales from low to high. Summing the scores of individual items produces a total score. The multidimensional self-report measures are used in about the same way, but people rate how worried (cognitive state anxiety) and how physiologically activated (somatic state anxiety) they feel, again using self-report scales ranging from low to high. Subscale scores for cognitive and somatic anxiety are obtained by summing scores for items representing each type of state anxiety. Sport-specific scales that measure state anxiety in sport have been developed to better predict one’s anxiety state in competitive sport settings. One example is the widely used Competitive State Anxiety Inventory–2 (CSAI-2), displayed here. Interestingly, besides having cognitive and somatic anxiety subscales, the CSAI- 2 also has a subscale of self-confidence, which is inversely related to cognitive and somatic anxiety.

In terms of measuring competitive trait anxiety, the first scale that was developed was the Sport Competition Anxiety Test. This is an unidimensional measure with only a single score ranging from 10 to 30. Although this is one of the most popular personality measures in sport psychology, sport psychologists now tend to use global and multidimensional self-reports to measure trait anxiety. The formats for these measures are similar to those for state anxiety assessments; however, instead of rating how anxious they feel right at that moment, people are asked how they typically feel. The components included somatic state anxiety (e.g., the degree to which one experiences heightened physical symptoms such as muscle tension), cognitive state anxiety (the degree to which one typically worries or has doubts) and concentration disruption (e.g., the degree to which one experiences concentration disruption during competition).

A direct relationship exists between a person’s levels of trait anxiety and state anxiety. Research has consistently shown that those who score high on trait anxiety measures also have more state anxiety in highly competitive, evaluative situations. This relationship is not perfect, however. A highly trait-anxious athlete may have a tremendous amount of experience in a particular situation and therefore not perceive a threat and the corresponding high state anxiety. Similarly, some highly trait-anxious people learn coping skills to help reduce the state anxiety they experience in evaluative situations. Still knowing a person’s level of trait anxiety is usually helpful in predicting how that person will react to competition, evaluation, and threatening conditions.

To make matters more complex, we know from anecdotal reports as well as research (e.g., that anxiety can fluctuate throughout competition.

For example, we often hear football players say that they felt very anxious before competition but settled down after the first hit. (Interestingly, it appears that somatic anxiety levels decrease rapidly when competition starts, and that cognitive anxiety levels change throughout competition.) Soccer players have reported that they did not feel anxious during a game, but that their anxiety level went “sky high” when they had to take a penalty kick at the end of the game. Future measures need to assess these changes in anxiety, although it is difficult to do so during a competition. One possible strategy is to retrospectively measure changes in anxiety. Research has indicated that athletes are quite good at assessing their state anxiety levels after the fact. For example, athletes could be asked within an hour of finishing a game how they felt at different times during the game.

To explore emotions and stressors throughout a competitive contest, researchers have used reflective diaries to help cricket players remember specific stressful situations, their appraisal of the situation, and reactions to it for five different games so that they would be able to respond with specifics during an in-depth interview. Results revealed that at the heart of the cricketers’ appraisal of potentially stressful and threatening situations were their perceived stress levels and emotional state. In addition, the appraisal process was closely attached to players’ personal values, beliefs, and commitment to achieving personal goals. For example, if a cricketer had performed well in the past in getting a specific batsman out, he appraised his chances of achieving personal goals as high in facing the same batsman again. In essence, he felt confident (not stressed) in attempting to attain his goals. Conversely, another bowler (pitcher) appraised facing a particular batsman as threatening if he had been unsuccessful in the past and therefore would feel stressed facing this batsman again.

Besides investigating changes in stress and emotions throughout a competition, researchers have also assessed changes in stress and subsequent coping strategies leading up to a competition. Specifically, Miles, Neil, and Barker (2016) investigated changes over a 7-day period before the first cricket game of the season. During this time, players were evaluated to determine who would make the starting lineup for the first competition. Results revealed the major competitive stressor for players early in the week was whether they would be selected to play (the need to display competence), but as players were selected, the stress on competition day shifted to performing well for their team. In addition, across the week before competition, the players continued to experience stressors that emanated from outside the sporting environment, which were termed organizational (e.g., team issues) and personal (e.g., relationships). Some of the major coping strategies used to deal with these stressors were social support, precompetition routines, self-talk, and humor for a detailed discussion of coping strategies).

Defining Stress and Understanding the Stress Process

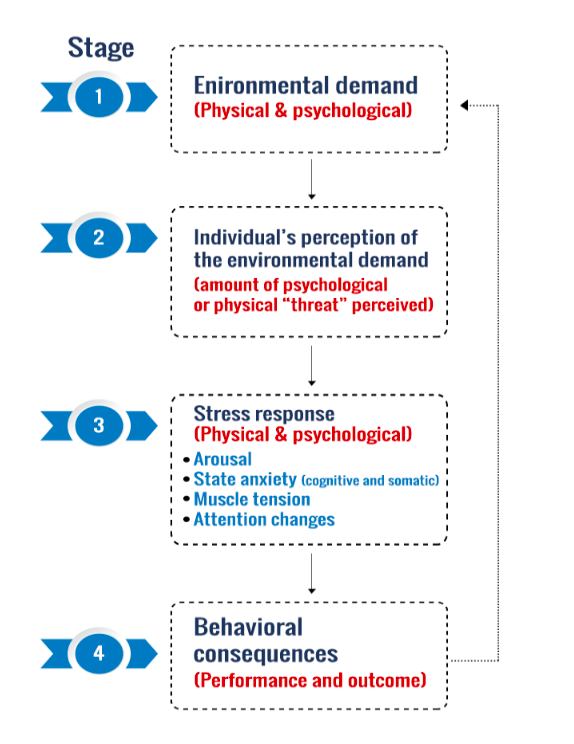

Stress is defined as “a substantial imbalance between demand (physical and/or psychological) and response capability, under conditions where failure to meet that demand has important consequences. It can also be described as a process or sequence of events that will leads to a unique outcome.

A very simple model that clarifies stress consists of four interrelated stages:

- Environmental demand

- Perception of demand

- Stress response

- Behavioral consequences

Stage 1: Environmental Demand

In the first stage of the stress process, some type of demand is placed on an individual. The demand might be physical, such as when a physical education student has to execute a newly learned volleyball skill in front of the class, or psychological, such as when parents are pressuring a young athlete to win a race.

Stage 2: Perception of Demand

The second stage of the stress process is the individual’s perception of stress from either physical or psychological demands. We do not always perceive the demands of life in the same way. For instance, one personality type might enjoy the attention of being in front of the class, whereas another type (an introvert, for example) may feel threatened. Incidentally, they could also both play on the same time in another environment or setting. When an athlete perceives disparity between the demands placed on them and being able to meet those demands, stress can emerge. The attention-grabbing personality might perceive no such imbalance or perceives it only to a nonthreatening degree.

A person’s level of trait anxiety greatly influences how that person perceives the world. Highly trait- anxious people tend to perceive more situations—especially evaluative and competitive ones—as threatening than people with lower trait anxiety do. For this reason, trait anxiety is an important influence in stage 2 of the stress process.

Stage 3: Stress Response

The third stage of the stress process is the individual’s physical and psychological response to a perception of the situation. If someone’s perception of an imbalance between demands and his response capability causes him to feel threatened, increased state anxiety results, bringing with it increased worries (cognitive state anxiety), heightened physiological activation (somatic state anxiety), or both. Other reactions, such as changes in concentration and increased muscle tension, accompany increased state anxiety as well.

Behavioral Consequences

The fourth stage is the actual behavior of the individual under stress. If a volleyball student perceives an imbalance between capability and demands and feels increased state anxiety, does performance deteriorate? Or does the increased state anxiety increase intensity of effort, thereby improving performance? The final stage of the stress process feeds back into the first. If a student becomes overly threatened and performs poorly in front of the class, the other children may laugh; this negative social evaluation becomes an additional demand on the child (stage 1). The stress process, then, becomes a continuing cycle.

Implications for Practice

The stress process has several implications for practice. If a corporate fitness specialist is asked by her company’s personnel director to help develop a stress management program for the company’s employees, for example, stage 1 of the model suggests that she should determine what demands are placed on the employees (e.g., increased workloads, unrealistic scheduling demands, hectic travel schedules). An analysis of stage 2 might lead her to question who is experiencing or perceiving the most stress (e.g., individuals in certain divisions or with certain jobs, or those with certain personality dispositions). Stage 3 would call for studying the reactions the employees are having to the increased stress: somatic state anxiety, cognitive state anxiety, or attention–concentration problems. Stage 4 analysis would focus on the subsequent behavior of employees feeling increased stress, such as greater absenteeism, reduced productivity, or decreased job satisfaction. By understanding this stress cycle, the fitness director can target her efforts to reduce stress. She might suggest physical activity (most likely in stage 3) or other means of stress management (e.g., time management seminars, restructured work schedules). She now has a better grasp of the specific causes and consequences of stress, which allows her to design more effective stress management activities.

Identifying Sources of Stress and Anxiety

There are thousands of specific sources of stress. Exercise psychologists have also shown that major life events such as a job change or a death in the family, as well as daily hassles such as an auto breakdown or a problem with a coworker, cause stress and affect physical and mental health (Berger, Weinberg, and Eklund, 2015). In athletes, stressors include performance issues such as worrying about performing up to capabilities, self-doubts about talent, and team selection; environmental issues such as financial costs, travel, and time needed for training; organizational issues such as coaching leadership and communication; physical danger; negative personal rapport behaviors of coaches; and relationships or traumatic experiences outside of sport, such as the death of a family member or negative interpersonal relationships. Researchers have concluded that athletes experience a core group of stress or strain sources that include competitive concerns, pressure to perform, lifestyle demands, and negative aspects of personal relationships. Additionally, injured elite athletes had psychological (e.g., fear, shattered hopes and dreams), physical, medical- or rehab-related, financial, and career stress sources along with missed opportunities outside the sport (e.g., inability to visit another country with the team).

Researchers have also examined sources of stress for coaches; these include such issues as communicating with athletes, recruiting, the pressure of having so many roles, and a lack of control over their athletes’ performance (Frey, 2007). Stress sources in physical therapists include high caseload, staff shortages, complexity of patient issues, and constant excessive workload (Lindsay, Hanson, Taylor, & McBurney, 2008). Finally, parental pressure (especially with young athletes) has been a traditional source of stress, although a study found that the climate in which the pressure is perceived can alter its effects. Specifically, researchers found that high pressure in a highly ego motivational climate (i.e., focus on outcome) increased perceptions of anxiety but high pressure in a highly mastery motivational climate (i.e., focus on improvement) decreased perceptions of anxiety. The many specific sources of stress for those participating in sport and physical activity contexts fall into some general categories determined by both situation and personality.

Situational Sources of Stress

Two common sources of situational stress exist. These general areas are the importance placed on an event or contest and the uncertainty that surrounds the outcome of that event.

Event Importance

In general, the more important the event, the more stress provoking. Thus, a championship contest is more stressful than a regular-season game, just as taking college boards is more stressful than taking a practice exam. Little League baseball players, for example, were observed each time they came to bat over an entire baseball season (Lowe, 1971). The batters’ heart rates were recorded while they were at bat and their nervous mannerisms on deck were observed. How critical the situation at bat was in the game (e.g., bases loaded, two outs, last inning, close score) and how important the game was in the season standings were both rated. The more critical the situation, the more stress and nervousness the young athletes exhibited.

The importance placed on an event is not always obvious, however. An event that may seem insignificant to most people may be very important for one particular person. For instance, a regular-season soccer game may not seem particularly important to most players on a team that has locked up a championship. Yet it may be of major importance to a particular player who is being observed by a college scout. You must continually assess the importance participants attach to activities.

Uncertainty

Uncertainty is a major situational source of stress, the greater the uncertainty, the greater the stress. Often, we cannot do anything about uncertainty. For example, when two evenly matched teams are scheduled to compete, there is maximum uncertainty, but little can or should be done about it. After all, the essence of sport is to put evenly matched athletes and teams together. However, at times teachers, coaches, and sports medicine professionals create unnecessary uncertainty by not informing participants of things such as the starting lineups, how to avoid injury in learning high-risk physical skills (e.g., vaulting in gymnastics), or what to expect while recovering from a serious athletic injury. Trainers, teachers, and coaches should be aware of how they might unknowingly create uncertainty in participants.

Uncertainty is not limited to the field or the gym. Athletes and recreational exercisers can have stress because of uncertainty in their lives in general. For example, a study of Australian football players found that uncertainties about one’s career, one’s future after football, relocation, and work and non-work conflicts were major stress sources (Noblet & Gifford, 2002). Similarly, many physical therapists and health and wellness professionals feel stressed because of the long hours and time away from family.

Personal Sources of Stress

Some people characterize situations as important and uncertain and view them with greater anxiety than other people do. Two personality dispositions that consistently relate to heightened state anxiety reactions are high trait anxiety and low self-esteem (Scanlan, 1986). A third important anxiety disposition in the context of exercise is social physique anxiety.

Trait Anxiety

As previously discussed, trait anxiety is a personality factor that predisposes a person to view competition and social evaluation as more or less threatening. A highly trait-anxious person perceives competition as more threatening and anxiety provoking than a lower trait-anxious person does. In fact, research shows that individuals with high trait anxiety have a cognitive bias to pick out more threat-related information in the same situation than their peers with low trait anxiety do.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is also related to perceptions of threat and corresponding changes in state anxiety. Athletes with low self-esteem, for example, have less confidence and more state anxiety than do athletes with high self-esteem. Strategies for enhancing self-confidence are important means of reducing the amount of state anxiety that individuals experience.

Social Physique Anxiety

Social physique anxiety is a personality disposition defined as the degree to which people become anxious when others observe their physiques. It reflects people’s tendency to become nervous or apprehensive when their body is being judged (or may be). Compared to people without this kind of anxiety, people with high social physique anxiety report experiencing more stress during fitness evaluations and which people sometimes performed better in front of an audience and other times performed worse. His observation was that the presence of an audience had a positive effect when people performed tasks that they knew well or that were simple, whereas their performance suffered when they performed less familiar or more complex tasks. Zajonc’s social facilitation theory contended that an audience creates arousal in the performer, which hurts performance on difficult tasks that are not yet learned but helps performance on well-learned tasks.

An audience need not be present for social facilitation to occur. The theory refers more broadly to the effects of the presence of others on performance, including co-action (two people performing simultaneously). Zajonc (1965) used drive theory to show that the presence of others increases arousal in the performer and that this increased arousal (drive) increases or brings out the performer’s dominant response (the most likely way to perform the skill). When people perform well-learned or simple skills (e.g., sit- ups), the dominant response is correct (positive performance) and the increased arousal facilitates performance. When people perform complex or unlearned skills (e.g., a novice golfer learning to drive a golf ball), the presence of others increases arousal and more often causes their dominant response to be incorrect (poorer performance). Thus, social facilitation theory predicts that an audience (i.e., coaction or the presence of others) inhibits performance on tasks that are complex or have not been learned thoroughly and enhances performance on tasks that are simple or have been learned well.

The implications are that you would want to eliminate audiences and evaluation as much as possible in learning situations. For example, if you were teaching a gymnastics routine, you would not want to expose youngsters to an audience too soon. It is critical to eliminate or lessen audience and co-action effects in learning environments to make them as arousal free as possible. However, when participants are performing well-learned or simple tasks, you might want to encourage people to come watch.

Although the drive and social facilitation theories explain how an audience can hurt performance when one is learning new skills, they do not explain so well how an audience affects a person’s performance of well-learned skills. These theories predict that as arousal increases, performance increases in a straight line. If this were true, we would expect highly skilled athletes to consistently excel in all high-pressure situations.

Yet nervousness and choking in the clutch occur even at the elite level. For this reason, we can only conclude that on well-learned skills, an audience may sometimes enhance performance and at other times inhibit it. The views presented next will give you a better understanding of how increased arousal or anxiety influences performance on well-learned tasks. In addition, “Home-Court Advantage: Myth or Reality” discusses what sport psychology researchers have learned about the home-field advantage—a topic related to both audience effects and the relationship between anxiety and performance.

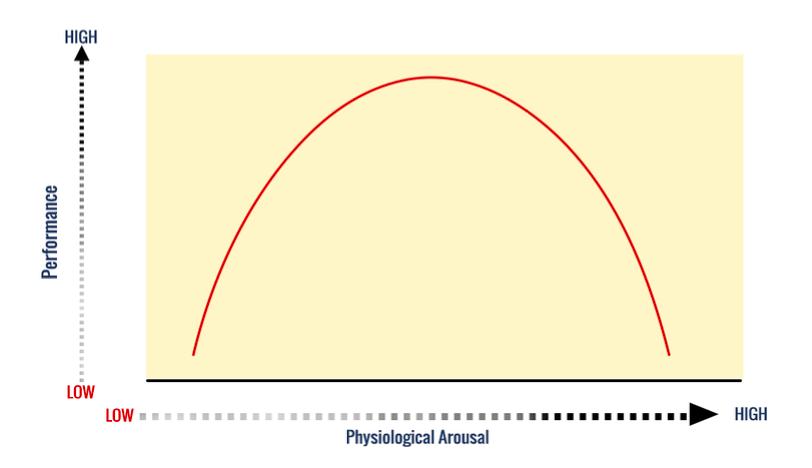

Inverted-U Hypothesis

Dissatisfied with the drive theory, most sport psychologists turned to the inverted-U hypothesis to explain the relationship between arousal states and performance (Landers & Arent, 2010). This view holds that at low arousal levels, performance will be below par; the exerciser or athlete is not psyched up. As arousal increases, so too does performance—up to an optimal point where best performance results. Further increases in arousal, however, cause performance to decline. This view is represented by an inverted U that reflects high performance with the optimal level of arousal and lesser performance with either low or very high arousal.

Most athletes and coaches accept the general notions of the inverted-U hypothesis. After all, most people have experienced underarousal, optimal arousal, and overarousal. However, despite the acceptance of the hypothesis in general and recent evidence supporting its predictions on relatively simple tasks, it has come under criticism (Mellalieu et al., 2006). Critics rightly question the shape of the arousal curve, ask whether optimal arousal always occurs at the midpoint of the arousal continuum, and question the nature of the arousal itself. In essence, the inverted U has taken us as far as it can, but now we need more explicit explanations. Hence, sport psychologists have begun to explore other views, hoping to more specifically understand the arousal–performance relationship.

Individualized Zones of Optimal Functioning

Yuri Hanin, a noted Russian sport psychologist, presented an alternative view called the individualized zones of optimal functioning (IZOF) model. Hanin (1997) found that top athletes have a zone of optimal state anxiety in which their best performance occurs. Outside this zone, poor

performance occurs. To underscore the importance of the IZOF model, researchers have conducted a historical review identifying 183 IZOF-based publications, making it one of the most widely applied models to study subjective experiences related to athletic performance.

Hanin’s IZOF view differs from the inverted-U hypothesis in two important ways:

- First, the optimal level of state anxiety does not always occur at the midpoint of the continuum but rather varies from individual to individual. That is, some athletes have a zone of optimal functioning at the lower end of the continuum, some in the midrange, and others at the upper end.

- Second, the optimal level of state anxiety is not a single point but a bandwidth. Thus, coaches and teachers should help participants identify and reach their own specific optimal zone of state anxiety.

However, despite the support that exists for the IZOF model, it has been criticized for its lack of explanation of why individual levels of anxiety may be beneficial or detrimental to performance.

The IZOF model has good support in the research literature. In addition, Hanin (2007) expanded the IZOF notion beyond anxiety to show how zones of optimal functioning use a variety of emotions and other psychobiosocial states, such as determination, pleasantness, and laziness. He concluded that for best performance to occur, athletes need individualized optimal levels not only of state anxiety but of a variety of other emotions as well. The IZOF view also contends that there are positive (e.g., confident, excited) and negative (e.g., fearful, nervous) emotions that enhance performance and positive (e.g., calm, comfortable) and negative (e.g., intense, annoyed) emotions that have a dysfunctional influence on performance. This development is important because it recognizes that a given emotion (e.g., anger) can be positively associated with performance for one person but negatively associated with performance for another. This idea of individualized profiling was highlighted in a study demonstrating that having athletes develop their own emotion-related states helped predict both successful and unsuccessful performance. A major coaching implication of the IZOF model, then, is that coaches must help each individual athlete achieve the ideal recipe of positive and negative emotions needed by that athlete for best performance.

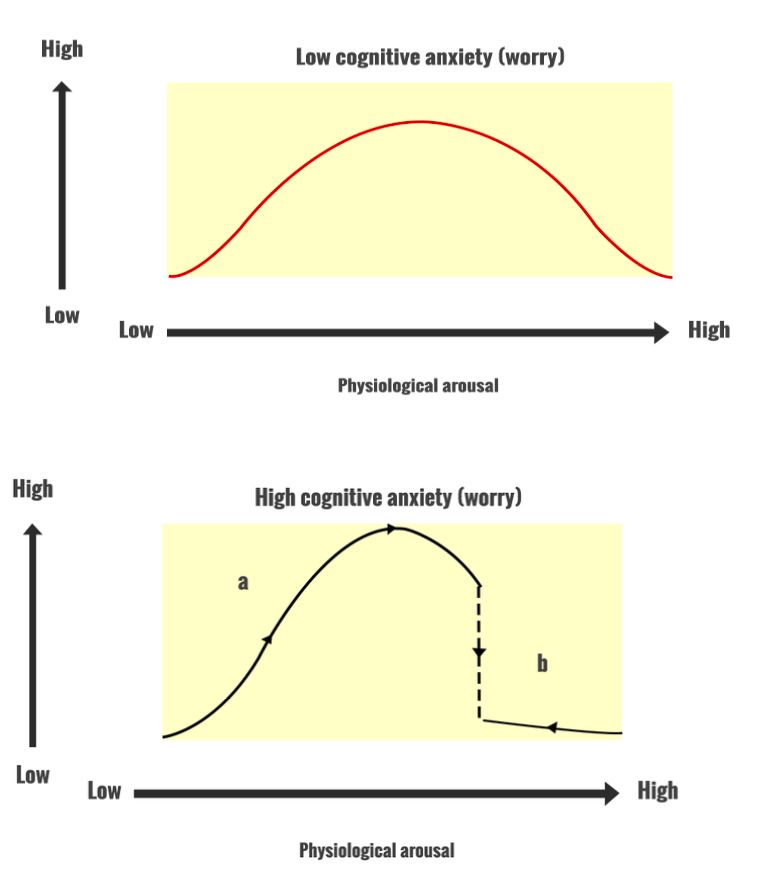

Multidimensional Anxiety Theory

Hanin’s IZOF hypothesis does not address whether the components of state anxiety (somatic and cognitive anxiety) affect performance in the same way. These state anxiety components are generally thought to influence performance differently; that is, physiological arousal (somatic state anxiety) and worry (cognitive state anxiety) affect performers differently. Your heart racing or pounding and your mind reiterating negative predictions, for instance, can affect you differentially.

Multidimensional anxiety theory predicts that cognitive state anxiety (worry) is negatively related to performance; that is, increases in cognitive state anxiety lead to decreases in performance. But the theory predicts that somatic state anxiety (which is physiologically manifested) is related to performance in an inverted U and that increases in anxiety facilitate performance up to an optimal level, beyond which additional anxiety causes performance to decline. Although studies have shown that these two anxiety components differentially predict performance, the precise predictions of multidimensional anxiety theory have not been consistently supported. One reason for this lack of support is the prediction that cognitive anxiety always has a detrimental effect on performance. The effect of cognitive anxiety (as well as somatic anxiety) on performance appears to be determined by a performer’s interpretation of anxiety, not just the amount or type of anxiety (Jones & Swain, 1992). Consequently, multidimensional anxiety theory has little support with respect to its performance predictions and is of little use in guiding practice.

Catastrophe Phenomenon

Hardy’s catastrophe view addresses another piece of the puzzle. According to his model, performance depends on the complex interaction of arousal and cognitive anxiety (Hardy, 1990, 1996). The catastrophe model predicts 90 that physiological arousal is related to performance in an inverted-U fashion, but only when an athlete is not worried or has low cognitive state anxiety. If cognitive anxiety is high (i.e., the athlete is worrying), however, the increases in arousal at some point reach a kind of threshold just past the point of optimal arousal level, and afterward a rapid decline in performance—the catastrophe— occurs. Therefore, physiological arousal (i.e., somatic anxiety) can have markedly different effects on performance depending on the amount of cognitive anxiety one is experiencing. Moreover, amid high worry, performance deteriorates dramatically once overarousal and the catastrophe occur. This is different from the steady decline predicted by the inverted-U hypothesis, and recovery takes longer.

The catastrophe model predicts that with low worry, increases in arousal or somatic anxiety are related to performance in an inverted-U manner. With great worry, the increases in arousal improve performance to an optimal threshold, beyond which additional arousal causes a catastrophic or rapid and dramatic decline in performance. In low-worry situations, arousal is related to performance in a traditional inverted-U fashion. However, overall performance is not as elevated as in the high-worry situation. Finally, under conditions of great worry, high levels of self-confidence allow performers to tolerate higher levels of arousal before they hit the point where they have a catastrophic drop in performance.

Under conditions of high cognitive anxiety as physiological arousal increases, performance also increases until an optimal arousal level is reached (marked a on the curve). After that point, however, a catastrophic decrease in performance occurs; the performer drops to a low level of performance (marked b on the curve). Once the athlete is at that part of the curve, he would need to greatly decrease his physiological arousal before being able to regain previous performance levels. The catastrophe model predicts, then, that after a catastrophic decrease in performance, the athlete must (a) completely relax physically, (b) cognitively restructure by controlling or eliminating worries and regaining confidence and control, and (c) reactivate or rouse himself in a controlled manner to again reach the optimal level of functioning. Doing all this is no easy task, so it is understandably very difficult to quickly recover from a catastrophic decrease in performance.

An athlete’s absolute performance level is higher under conditions of high cognitive anxiety than under conditions of low cognitive anxiety. This shows that cognitive anxiety or worry is not necessarily bad or detrimental to performance. In fact, this model predicts that you will perform better with some worry, provided that your physiological arousal level does not go too high (i.e., a little bit of stress heightens an athlete’s effort and narrows attention, giving the individual an edge over other performers). Performance deteriorates only under the combined conditions of high worry plus high physiological arousal.

Although some scientific support exists for the catastrophe model, it is difficult to scientifically test and to date, evidence for it is equivocal. Still, you can derive from it an important message for practice, namely that an ideal physiological arousal level isn’t enough for optimal performance; it is also necessary to manage or control cognitive state anxiety (worrying).

Reversal Theory

Kerr’s application of reversal theory contends that the way in which arousal affects performance depends on an individual’s interpretation of his or her arousal level. Jose might interpret high arousal as a pleasant excitement, whereas

Isabelle might interpret it as an unpleasant anxiety. She might see low arousal as relaxation, whereas Jose sees it as boring. Athletes are thought to make quick shifts—“reversals”—in their interpretations of arousal. An athlete may perceive arousal as positive one minute and then reverse the interpretation to negative the next minute. Reversal theory predicts that for best performance, athletes must interpret their arousal as pleasant excitement rather than as unpleasant anxiety.

Reversal theory’s key contributions to our understanding of the arousal–performance relationship are twofold. First, reversal theory emphasizes that one’s interpretation of arousal— not just the amount of arousal one feels—is significant; second, the theory holds that performers can shift or reverse their positive or negative interpretations of arousal from moment to moment. Reversal theory offers an interesting alternative to previous views of the arousal– performance relationship. However, few have tested the theory’s predictions, so firm conclusions cannot be made about the scientific predictions.

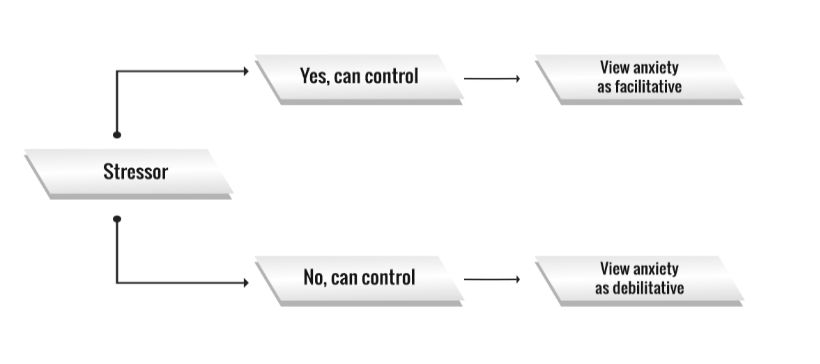

Anxiety and Intensity

For many years, most researchers assumed that anxiety had only negative effects on performance. People can view anxiety symptoms either as positive and helpful to performance (facilitative) or as negative and harmful to performance (debilitative). To fully understand the anxiety–performance relationship, you must examine both the intensity of a person’s anxiety (how much anxiety the person feels) and its direction (his interpretation of that anxiety as facilitative or debilitative to performance). Jones and colleagues contended that viewing anxiety as facilitative leads to superior performance, whereas viewing it as debilitative leads to poor performance.

How much stress an athlete can have depends on individual factors such as her trait anxiety or self-esteem. Most important, whether the resulting state anxiety is perceived as facilitative or debilitative depends on how much control the athlete perceives. If the runner feels in control (e.g., that she can cope with the anxiety and that running a certain time in the race is possible), then facilitative anxiety will result. However, if she believes that there is no way she can run a competitive time and that she can’t cope with the pressure, debilitative anxiety occurs. The athlete’s perception of control relative to coping and goal attainment is critical, then, in determining whether state anxiety will be viewed as facilitative or debilitative.

Related to perceptions of control is whether the athlete views the situation as a challenge or threat. For example, research has found that when athletes viewed a pressurized situation as a challenge (i.e., they had the resources and coping skills to meet the demands placed on them) rather than a threat (i.e., they did not have the resources and coping skills to meet the demands placed on them) they exhibited increases in performance. Viewing the situation as a challenge also produced lower levels of cognitive and somatic anxiety and produced more focused attentional processes. Therefore, athletes’ perception that they have the resources to control the situation produces a variety of positive responses.

Sport psychologists have already found support for this association between how anxiety is perceived and performance level. For example, good performances on the balance beam have been associated with gymnasts interpreting cognitive anxiety as facilitative. Similarly, elite swimmers have reported both cognitive and somatic anxiety as more facilitative and less debilitative than have nonelite swimmers. In addition, researchers found that elite swimmers were able to consistently maintain a facilitative interpretation of anxiety, especially through using psychological skills such as goal setting, imagery, and self-talk. In essence, performers can be trained to effectively use their anxiety symptoms in a productive way and to develop a rational appraisal process in relation to their experiences during competition.

Although these results suggest that using relaxation to reduce the intensity of anxiety may not always be appropriate, athletes should learn a repertoire of psychological skills to help interpret anxiety symptoms as facilitative. The interpretation of anxiety being facilitating may not be what enhances performance per se; rather, they argue that the positive emotion of excitement might enhance performance. Whereas most previous studies measured only the construct of anxiety, they measured both anxiety and excitement in their study. Future studies should assess other positive emotions (e.g., excitement, happiness, hope, pride) along with anxiety and other negative emotions (e.g., shame, sadness, guilt, anger) to determine what has the greatest influence on performance.

It is also important to note that a range of personal and situational variables may influence the directional response. Some of these personal factors include trait anxiety, neuroticism, extraversion, achievement motivation, hardiness, self-confidence, sex, coping strategies, and psychological skills. A study indicated that of all the personal variables, trait anxiety was the most important predictor of the directional response employed by athletes. The situational variables that influence the interpretation of anxiety include competitive experience, skill level, goal attainment, expectations, sport type, and performance. The individual difference variable that has most consistently determined whether anxiety is interpreted as facilitative or debilitative has been skill level. Specifically, elite performers interpret their anxiety symptoms as more facilitative and report higher levels of self- confidence than their nonelite counterparts do. Studies have revealed that these elite athletes maintain a facilitative perspective as well as high levels of confidence through rationalizing thoughts and feelings before competing via the combined use of such psychological skills as self-talk, imagery, and goal setting.

In summary, how an athlete interprets the direction of anxiety (as facilitative or debilitative) has a significant effect on the anxiety– performance relationship. Athletes can learn psychological skills that allow them to interpret their anxiety as facilitative. It follows that coaches should try to help athletes view increased arousal and anxiety as conditions of excitement instead of fear. Certified Sports Psychology Coaches should also do everything possible to help athletes develop perceptions of control through enhancing confidence and through psychological skills training.

Frequency of Anxiety

Compared to direction of anxiety, frequency of anxiety has received little attention in the sport psychology literature. It seems intuitive that the frequency with which athletes have anxiety symptoms (especially ones that are interpreted as debilitating) is an important component of the anxiety response and its effect on performance.

For example, researchers found that athletes who viewed anxiety as facilitative had lower frequencies of cognitive anxiety and higher frequencies of self-confidence throughout the precompetition period than did athletes who viewed their anxiety as debilitating. From a coaching perspective, a coach would want to know how often (and when) an athlete feels anxiety symptoms, not just how intense the symptoms are and how they are interpreted. For example, a soccer player may rarely have anxiety symptoms but does so when he is chosen to take a penalty kick. Knowing both how frequently and in what situations a player has anxiety that would be debilitative is helpful for coaches in choosing to play certain players in certain situations.

Significance of Arousal– Performance Views

There is certainly no shortage of arousal– performance views—there are so many that it is easy to get confused. So, let’s summarize what these views tell us regarding practice. The IZOF, multidimensional anxiety, catastrophe, reversal, and direction and intensity views offer several:

- Arousal is a multifaceted phenomenon consisting of both physiological activation and an athlete’s interpretation of that activation (e.g., state anxiety, confidence, facilitative anxiety). We must help performers find the optimal mix of these emotions for best performance. Moreover, these optimal mixes of arousal-related emotions are highly individual and task specific. Two athletes participating in the same event may not have the same optimal emotional arousal level, and a person’s optimal emotional arousal level for performing a balance beam routine would be quite different from the optimal arousal level for a maximum bench press in power weightlifting.

- Arousal and state anxiety do not necessarily have a negative effect on performance. The effects can be positive and facilitative or negative and debilitative, depending largely on how the performer interprets changes. In addition, self- confidence and enhanced perceptions of control are critical to facilitating heightened arousal as positive (psyching up) as opposed to negative (psyching out).

- Some optimal level of arousal and emotion leads to peak performance, but the optimal levels of physiological activation and arousal-related thoughts (worry) are not necessarily the same!

- Both the catastrophe and reversal theories suggest that the interaction between levels of physiological activation and arousal-related thoughts appears to be more important than absolute levels of each. Some people perform best with relatively low optimal arousal and state anxiety, whereas others perform their best with higher levels.

- An optimal level of arousal is thought to be related to peak performance, but it is doubtful that this level occurs at the midpoint of the arousal continuum. Excessive arousal likely does not cause slow, gradual declines in performance but rather “catastrophes” that are difficult to reverse.

- Strategies for psyching up should be used with caution because it is difficult for athletes to recover once they have a performance catastrophe.

- Athletes should have well-practiced self-talk, imagery, and goal-setting skills for coping with anxiety. They must also perceive performance goals to be truly attainable.

Why Arousal Influences Performance

Understanding why arousal affects performance can help you regulate arousal, both in yourself and in others. For instance, if heightened arousal and state anxiety lead to increased muscle tension in Nicole, a golfer, then progressive muscle relaxation techniques may reduce her state anxiety and improve performance. Thought control strategies, however, may work better for Shane, another golfer, who needs to control excessive cognitive state anxiety.

At least two things explain how increased arousal influences athletic performance:

- Increased muscle tension, fatigue, and coordination difficulties

- Changes in attention, concentration, and visual search patterns

Muscle Tension, Fatigue, and Coordination

Difficulties Many people who have great stress report muscle soreness, aches, and pains. Athletes who have high levels of state anxiety might say, “I don’t feel right,” “My body doesn’t seem to follow directions,” or “I tensed up” in critical situations. Comments like these are natural: Increases in arousal and state anxiety cause increases in muscle tension and can interfere with coordination.

For example, some highly trait-anxious and lower trait-anxious college students were watched closely as they threw tennis balls at a target. As you might expect, the higher trait-anxious students had considerably more state anxiety than the lower trait-anxious participants had (Weinberg & Hunt, 1976). Moreover, electroencephalograms monitoring electrical activity in the students’ muscles showed that increased state anxiety caused the highly anxious individuals to use more muscular energy before, during, and after their throws. Similarly, in a study of novice rock climbers traversing an identical route under high-height versus low-height conditions, participants had increased muscle fatigue and blood lactate concentrations when performing in the high-anxiety height condition (Pijpers, Oudejans, Holsheimer, & Bakker, 2003). Thus, these studies show that increased muscle tension, fatigue, and coordination difficulties contributed to the students’ and athletes’ inferior performances under high-stress conditions.

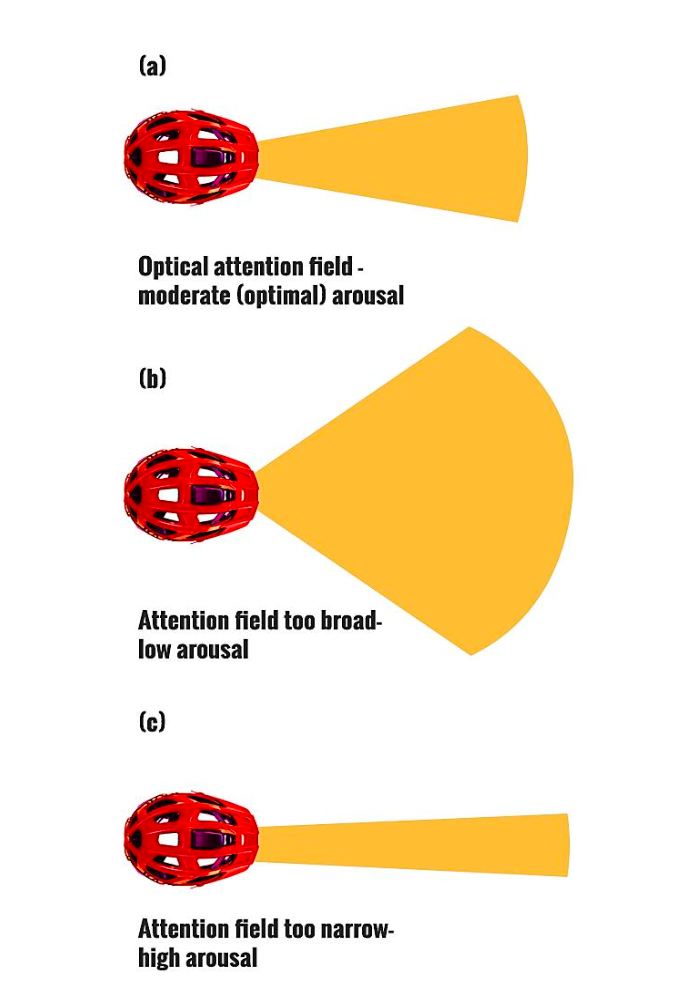

Attention, Concentration, and….

Increased arousal and state anxiety also influence athletic performance through changes in attention, concentration, and visual search patterns (Janelle, 2002; Wilson, 2010). First, increased arousal narrows a performer’s attentional field. (For example, Tamika is a goalie in ice hockey and needs to maintain a broad but optimal focus of attention as three opponents break into her end of the ice. If she becomes preoccupied with Sandra, who has the puck, and does not attend to the other players on the periphery, Sandra will simply pass off to a teammate on the wing for an easy score. Under normal conditions, Tamika can maintain her optimal attentional focus but if she is underaroused her attentional focus may be too broad, taking in both task-relevant (e.g., the opposing players) and irrelevant (e.g., the crowd) cues. When she has excessive levels of arousal and state anxiety, however, her attentional focus narrows too much and she is unable to survey the entire playing surface. For example, an athlete who had severe anxiety problems might say the following: “When the pressure is on, it’s like I’m looking through the tube in a roll of toilet paper.” In psychological terms, increased arousal causes a narrowing of the attentional field, which negatively influences performance on tasks requiring a broad external focus.

When arousal is increased, performers also tend to scan the playing environment less often. For example, Tony is a wrestler who has high levels of arousal and state anxiety. He becomes preoccupied with executing one move on an opponent and does not visually or kinetically scan the opponent’s total body position for other potential opportunities. Thus, Tony’s performance deteriorates as he scans less often, and potential scoring opportunities consequently go undetected. Arousal and state anxiety also cause changes in attention and concentration levels by affecting attention style. Athletes must learn to shift their attention to appropriate task cues. For example, a quarterback in football needs to shift from a broad external span when surveying the field for open receivers to a narrow external focus when delivering a pass. Each individual also has a dominant attention style.

Increased arousal can cause performers to shift to a dominant attention style that may be inappropriate for the skill at hand. Increased arousal and state anxiety also cause athletes to attend to inappropriate cues. For instance, most athletes perform well-learned skills best when they fully concentrate on the task. Unaware of their levels of concentration, they perform on automatic pilot or in a “flow zone”. Unfortunately, excessive cognitive state anxiety sometimes causes performers to focus on inappropriate task cues by “worrying about worrying” and becoming overly self-conscious. This, in turn, affects optimal concentration. In addition, other researchers have shown that three types of thoughts are tied to cognitive interference for athletes: performance worries, situation-irrelevant thoughts, and thoughts of escape.

Research has also shown that visual cues are differentially identified and processed when performers are anxious. In studying karate participants, research has shown that increased anxiety influences attention via changes in visual search patterns. Study in this area also showed that increased anxiety is associated with alterations in gaze tendencies and eye fixations. In a study using basketball free-throw shooting, shooters performed under conditions of either high or low threat of evaluation, and their efficiency of eye gaze (the final visual fixation on the target before physical movement) was assessed. As expected, participants in the high- stress condition shot less well and had a significant reduction in the “quiet eye” period just before the shot. (Longer fixations are better.) This shows that anxiety influences performance by disrupting the visual attention of shooters. However, quiet-eye training has been shown to increase performance.

Finally, the complexity in the way anxiety influences sport performance is reflected in the processing efficiency. This theory contends that increased anxiety interferes with working memory resources. In the short run, this does not negatively influence performance because the athlete makes up for the deficits caused by the anxiety by increasing her effort. However, as anxiety increases, the benefits of increased effort are often outweighed by the reduced attentional capacity (processing inefficiency) that comes with heightened anxiety. Thus, anxiety may initially result in increased performance because of increases in effort, but the attentional deficits will overcome any increases in effort when the anxiety rises high enough.

What all these studies show, then, is that the relationship between increased anxiety and attention or thought control is a key mechanism for explaining the arousal–performance relationship.

Applying Knowledge to Professional Practice

You can integrate your knowledge of arousal, stress, and anxiety by considering its implications for professional practice. Four of the most important guidelines are to:

- identify the optimal combination of arousal-r elated emotions needed for best performance;

- recognize how personal and situational factors interact to influence arousal, anxiety, and performance;

- recognize the signs of increased arousal and anxiety in sport and exercise participants; and

- tailor coaching and instructional practices to individuals.

Identify Optimal Arousal-Related Emotions

One of the most effective ways to help people achieve peak performance is to increase their awareness of how arousal-related emotions can lead to peak performances. Once this is accomplished, teaching athletes various psychological strategies (e.g., using imagery and developing pre-performance routines) can help them regulate arousal.

Think of arousal as an emotional temperature and arousal-regulation skills as a thermostat. The athlete’s goals are to identify the optimal emotional temperature for his best performance and then to learn how to set his thermostat to this temperature—either by raising (psyching up) or lowering (chilling out) his emotional temperature. For example, a study by Rathschlag and Memmert (2013) found that athletes can induce emotions, and that certain emotions such as anger and happiness can lead to increased performance, whereas sadness and anxiety can lead to decreased performance.

Recognize the Interaction of Personal and Situational Factors

Like other behaviors, stress and anxiety can best be understood and predicted by considering the interaction of personal and situational factors. For instance, many people mistakenly assume that the low trait-anxious athlete will always be the best performer because she will achieve an optimal level of state anxiety and arousal needed for competition. In contrast, the assumption is that the highly trait-anxious athlete will consistently choke. But this is not the case.

Where the importance placed on performance is not excessive and some certainty exists about the outcome, you might expect a swimmer with high trait anxiety to experience elevated arousal and state anxiety because he is predisposed to perceiving most competitive situations as somewhat threatening. It seems likely that he would move close to his optimal level of arousal and state anxiety. In contrast, a competitor with low trait anxiety may not perceive the situation as very important because she does not feel threatened. Hence, her level of arousal and her state anxiety remain low, and she has trouble achieving an optimal performance.

In a high-pressure situation, in which the meet has considerable importance, and the outcome is highly uncertain, these same swimmers react quite differently. The higher trait-anxious swimmer perceives this situation as even more important than it is and responds with very high levels of arousal and state anxiety: He overshoots his optimal level of state anxiety and arousal. The low trait-anxious swimmer also has increased state anxiety, but because she tends to perceive competition and social evaluation as less threatening, her state anxiety and arousal will likely be in an optimal range. The interaction of personal factors (e.g., self-esteem, social physique anxiety, and trait anxiety) and situational factors (e.g., event importance and uncertainty) is a better predictor of arousal, state anxiety, and performance than either set of these factors alone.

Recognize Arousal and State Anxiety Signs

The interactional approach has several implications for helping exercise and sport participants manage stress. Chief among these implications is the need to identify people who are experiencing heightened stress and anxiety. This is not easy to do.

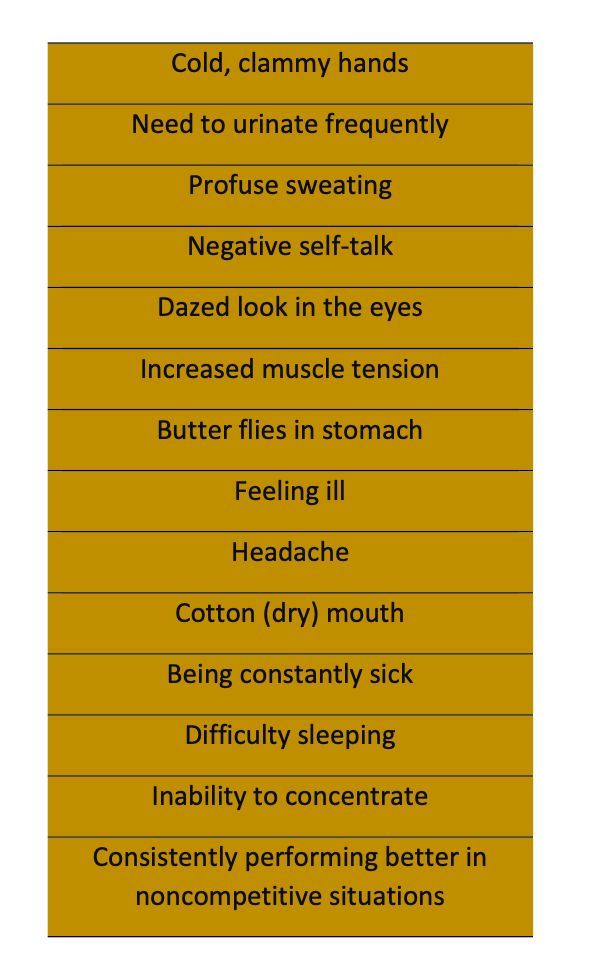

You can more accurately detect a person’s anxiety levels if you are familiar with the signs and symptoms of increased stress and anxiety:

Although no specific number or pattern of symptoms characterizes a high level of stress, people who have high levels of state anxiety often exhibit several of the signs listed. The key is to notice changes in these variables between high- and low-stress environments (e.g., when a normally positive athlete becomes negative).

One of the best (although often overlooked) ways to understand what people are feeling is to ask them! Encourage your participants to talk freely with you about their feelings. Be empathic by trying to see things from their perspectives (i.e., thinking of how you would eel in their situation at their level of experience). This allows you to associate specific behavioral patterns with varying levels of stress and anxiety and to better read people’s anxiety levels.

Tailor Coaching Strategies to Individuals

Individualize teaching, exercise, and coaching practices. At times arousal and state anxiety levels need to be reduced, at other times maintained, and at still other times facilitated. The teacher or coach should recognize when and in whom arousal and state anxiety need to be enhanced, reduced, or maintained.

For example, if a student or athlete with high trait anxiety and low self-esteem must perform in a highly evaluative environment, the teacher or coach would best de-emphasize the importance of the situation and instead emphasize the performer’s preparation. A pep talk stressing the importance of the situation and of performing well would only add stress and increase arousal and state anxiety beyond an optimal level. Someone with moderate levels of trait anxiety and self- esteem may be best left alone in the same highly evaluative situation. This individual’s arousal and state anxiety would probably be elevated but not excessive. However, an athlete with very low trait anxiety and high self-esteem may need a pep talk to increase arousal before performing in a nonthreatening environment.

Instructors who have students or clients with high social physique anxiety should encourage these exercisers to wear clothes that cover their bodies. Instructors can also minimize social evaluation of physiques by creating settings that eliminate observation by passersby.

Summary

- Discuss the nature of stress and anxiety (what the y are and how they are measured). Stress, arousal, and anxiety each have distinct meanings. Stress is a process that occurs when people perceive an imbalance between the physical and psychological demands on them and their ability to respond. Arousal is the blend of physiological and psychological activity in a person that varies on a continuum from deep sleep to intense excitement. Anxiety is a negative emotional state characterized by feelings of nervousness, worry, and apprehension associated with activation or arousal of the body. It consists of cognitive, somatic, trait, and state components.

- Identify the major sources of anxiety and stress. Some situations produce more state anxiety and arousal than others (e.g., events that are important and in which the outcome is uncertain). Stress is also influenced by personality dispositions (e.g., trait anxiety and self-esteem). Individuals with high trait anxiety, low self-esteem, and high social physique anxiety have more state anxiety than others.

- Explain how and why arousal- and anxiety-r elated emotions affect performance. Arousal-related emotions, such as cognitive and somatic state anxiety, are related to performance. Arousal and anxiety influence performance by inducing changes in attention and concentration and by increasing muscle

Review and Discuss

- Distinguish between the terms arousal, state anxiety, trait anxiety, cognitive state anxiety, and somatic state anxiety.

- Define stress and identify the f our stages of the stress process. Why are these stages important? How can they guide practice?

- What are t wo or three major sources of situational and personal stress?

- What is social facilitation theory? What implications does this theory have for practice?

- Discuss the major differences in how arousal relates to performance according to the following theories: • Drive theory • Inverted-U hypothesis • Individualized zones of optimal functioning • Multidimensional anxiety theory • Catastrophe model • Reversal theory • Anxiety direction and intensity view

- Describe the major signs of increased state anxiety in athletes.

Are you ready to begin your professional certification training in this field?

Click here for details >>>>