Today’s society is mechanized and computerized. People spend substantial time in front of their computers (work or personal) which can exacerbate one’s proper alignment (this includes the numerous computer games along with cell phone communication (texting) which lead to increased risk of poor posture).

Today’s society is mechanized and computerized. People spend substantial time in front of their computers (work or personal) which can exacerbate one’s proper alignment (this includes the numerous computer games along with cell phone communication (texting) which lead to increased risk of poor posture).

Students of all ages and even the professionally employed foster poor postural habits with heavy backpacks for carrying items necessary for their success at school or work. This visual perspective may identify some causes of poor posture. Postural assessments serve as flexibility assessments while also defining or pinpointing muscular weak points. By posture, we are referring to the position of one’s body in space.

How the individual positions their body at any one moment in time is their posture at that moment. When they have found an alignment which they revert to while standing, this is their current static posture. How they position themselves as they move is referred to as dynamic posture.

Instead of referring to posture as either good or bad, it is better to think of it as ideal or not ideal. Different situations will call upon different expectations for movement and bodily positions.

Ideal posture is the position of the body at any moment in time with the least risk for injury or joint dysfunction. Ideal posture is a state of musculoskeletal body balance or bodily musculoskeletal equilibrium. An individual’s ability to maintain control over their posture and maintain this equilibrium is their level of postural control. An individual may slouch or sit unevenly for a period of time but may be able to attain ideal posture at a moment’s notice.

It is important for you as a coach or personal trainer to recognize that all postural positions from one individual to the next are just that – individual. There are certain guides or norms for ideal posture but they will vary depending upon the joint mobility/stability and bone configurations of the individual.

For our purposes here, we will refer to neutral alignment as the ideal posture. Neutral alignment is a position directly between extremes of motion at a joint. While standing, anatomical neutral is a position with hands at the sides and palms facing the body. This differs from the anatomical position with palms facing forward (external rotation at wrist or supination).

Static Posture

The static posture assessment is a simple way of quickly assessing the client’s recognition of body position in space. Not being aware of or not being able to control body position can be severely detrimental to performance. The coach or personal trainer is not looking for perfect posture (no such posture exists).

Coaches and personal trainers should be looking for gross abnormalities from an anatomically neutral position that could cause future injury (or worsening current injury) or influence performance (through a waste of energy innervating muscles at the wrong time or that should not be active at a particular moment).

The job of the coach/trainer is not to nit-pick the smallest of details. The job of the coach/trainer (for the static posture test) is to take note of perceived gross abnormalities in posture. These abnormalities should be written down for later review especially when teaching basic exercises chosen for the individualized training program.

Ideal Posture

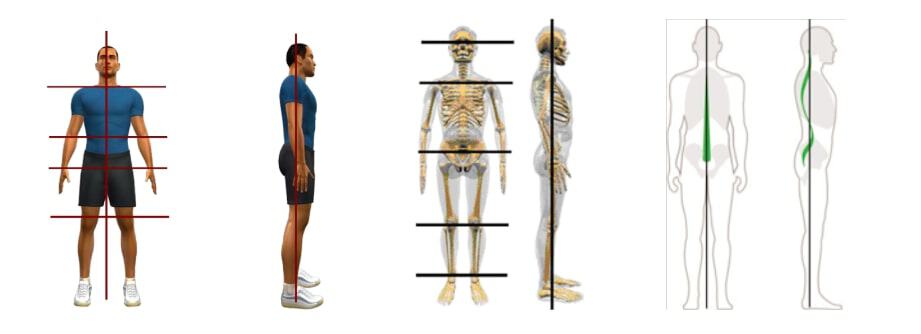

A plumb line should be able to be drawn through the ear, shoulder, hip knee and ankle (malleolus) from the side and directly down the middle of the body from the front or back with equal weight and body proportions to each side. If neutral is not able to be accomplished without queuing or external recognition from an outside viewpoint, a muscular imbalance is a likely present.

Here is the desired view for ideal posture (full body views front and lateral aspects).

What to look for in “ideal posture”

What to look for in “ideal posture”

Back and Front Views – the standard “line of reference” represent a projection of the gravity line in the midsagittal plane (dividing the body into equal left and right halves). Beginning midway between the heels, it extends upward midway between the lower extremities, through the mid-line of the pelvis, spine, sternum, and skull. The right and left halves of all the structures shown are essentially symmetrical, and by hypothesis, the two halves of the body counter-balance.

In the Side View, the standard line of reference (plumb line) represents a projection of the gravity line in what is called the Frontal Plane. This plane hypothetically divides the body into front and back sections of equal weight. These sections are not symmetrical, and no line of division is obvious on the basis of anatomical structures.

In performing the static posture assessment:

Have the client stand relaxed

If the client appears to be standing in a position that shows awareness of being assessed rather than a natural posture, have the client march in place for 10-20 seconds and then relax to find a more natural rather than practiced posture

Observe the client for 20-30 seconds maximum from each of four viewpoints (anterior, lateral left, lateral right, and posterior).

Take no longer than 1-2 minutes for the entire posture assessment

Make note of gross abnormalities from anatomical neutral for the:

- Head/Neck (Cervical Spine)

- Shoulders (Glenohumeral Joints)

- Shoulder Blades (Scapulae)

- Middle and Lower Spine (Thoracic and

- Lumbar Vertebrae)

- Hips (Acetabulofemoral Joints)

- Knees (Patellofemoral/Tibiofemoral Joints)

- Ankles (Talocrural Joints)

- Note deviations with brief descriptions (such as “slight cervical lateral flexion left” or “slight head/neck lean left”)

Four Types of Postural Alignment

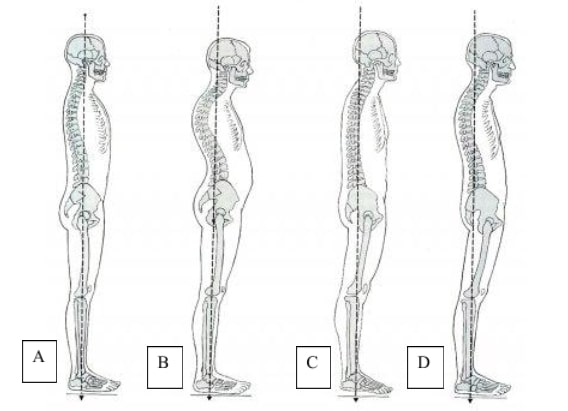

The normal curves of the spine consist of a curve that is convex forward in the neck (cervical region), a curve that is convex in the upper back (thoracic region), and a curve that is convex forward in the low back (lumbar region). These may be described as a slight extension of the neck, slight flexion of the upper back, and a slight extension of the low back.

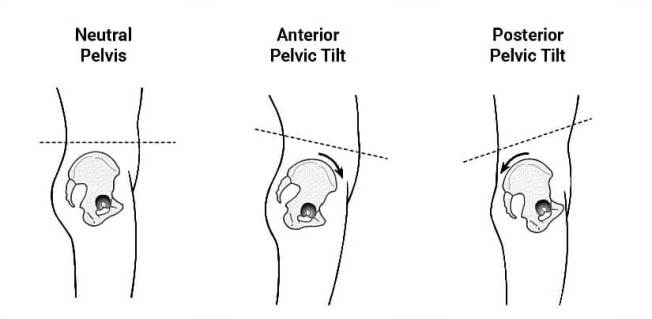

When there is a normal curve in the low back, the pelvis is in a neutral position. In a faulty postural position, the pelvis may be in an anterior, posterior, or lateral tilt. Any tilting of the pelvis involves simultaneous movements of the low back and hip joints.

Please also note numerous variations of these positions may exist depending on the individual, therefore, you must be aware of the deviations from the basic “ideal” alignment (front, lateral, and posterior views) to identify the root causes of these deviations and how they affect movement.

- Figure A – the bony prominences at the front of the pelvis are in a neutral position, as indicated by the anterior-superior iliac spines and the symphysis pubis being in the same vertical plane.

- Figure B – Anterior tilt position: the pelvis tilts forward, decreasing the angle between the pelvis and the thigh anteriorly, resulting in flexion of the hip joint; the low back arches forward, creating an increased forward curve (lordosis) in the low back

- Figure C and D – posterior pelvic tilt. The pelvis tilts backward, the hip joints extend, and the low back flattens.

Pelvic Tilt

The pelvis is a segmental link which “bridges” the vertebral column ay the sacrum (tailbone) and the lower extremity at the femur (thigh bone). During weight bearing, the lower extremity is somewhat fixed (non-moving). The pelvis is free to flex or extend relative to the femur. If the pelvis flexes or extends relative to the femur, the vertebral column must realign itself relative to the pelvis. The two figures below show the relation of the vertebral column and the different positions of the pelvis relative to the vertebral column. The three common positions of the pelvis are neutral (normal), anterior tilt, and posterior tilt.

When performing a postural analysis, the primary concern is to identify/observe how “altered” the prospective trainee’s posture is from normal. This includes observing not only one’s pelvis position but the entire vertebral column’s position and these two segments intimately interact. The coach or trainer must observe all of these positions from numerous viewpoints as well (front, back, and lateral viewpoints). The initial postural analysis is your starting point to determine if there is any alteration(s) in these two sections during dynamic movement.

How You Can Help

Check out what it takes to start a career in personal fitness training. This is your most affordable and fastest way to become a highly qualified personal trainer.

There is always something exciting about earning a new training or coaching certification and applying that new knowledge of how you train your clients. This also helps you hit the reset button.

NESTA coaching programs are open to anyone with a desire to learn and help others. There are no prerequisites.

That’s it for now.

Take action!

PS: Click here to see many helpful business/career resources